item details

Overview

This essay originally appeared in New Zealand Art at Te Papa (Te Papa Press, 2018).

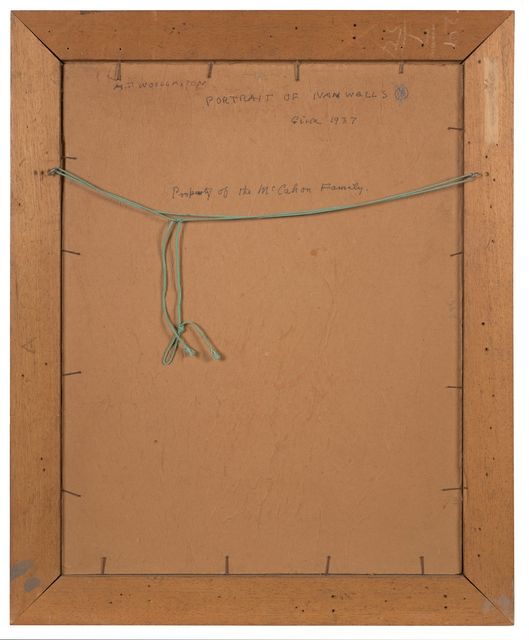

Toss Woollaston painted Portrait of Ivan Wells around 1936, when he was experimenting with the modernist portrait. The subject was the twelve-year-old son of his employer, orchardist Decimus Wells, who had allowed him to build a cottage on his land at Māpua, near Nelson. Woollaston often attended musical evenings at the Wells home to draw family members. Ivan was a frequent model, earning sixpence an hour for his efforts.

Woollaston had discovered modernism as a young man in the early 1930s, enthralled by the paintings of English migrant Robert N Field. In 1934 he took lessons from Flora Scales, a New Zealand artist who had studied in Germany. She encouraged him to abandon traditional perspective and treat painting as a dynamic arrangement of overlapping and rotating planes, held in balance by carefully calibrated colour. She also let him see her lecture notes from the Hans Hofmann School in Munich. Hofmann had dismissed the idea that painting should attempt to imitate the appearance of nature: instead, artists should engage in a much more powerful and creative act, infusing their work with new, independent life.

This is the heady, liberating atmosphere in which Woollaston painted this image, one of a series of portraits that privilege spontaneity and expression over naturalism and conventional finish. It could be described as a painted drawing, with its bold conté outlines and sketchy, summary treatment. The three floating, overlapping heads are stylised to varying degrees, closely if unintentionally echoing the photography of Cecil Beaton at exactly this time, while the third one — strangely inverted — has a mask-like quality, suggesting the influence of Picasso. Portrait of Ivan Wells declares Woollaston’s modernist allegiances and his commitment to experimentation.

Paintings like this would have seemed startling in 1930s New Zealand, when a naturalistic style of portraiture by such figures as Linley Richardson and Elizabeth Kelly dominated the art scene. One of the first to appreciate Woollaston’s modernism was the young Dunedin painter Colin McCahon, who acquired Portrait of Ivan Wells and retained it all his life. McCahon also owned another key early Woollaston portrait, Figures from life, 1936, and when he gave it to the Auckland City Art Gallery in 1954, it was the first Woollaston to enter a public collection.

Jill Trevelyan

In Toss Woollaston’s enigmatic Portrait of Ivan Wells the artist has simplified and flattened the face of a young boy, boldly outlining it in black conté to give it a mask-like appearance. He repeats the head three times, flipping one upside down and layering the faces over each other to create a very peculiar sense of space.

Painted around 1937, this work was one of the most striking and decisive steps toward modernism that had ever been made in New Zealand thus far. Woollaston painted it at the high point of his early experiments with modernist painting, following his first solo exhibition in Dunedin in 1936. The work declares the artist’s modernist allegiances, and the mask-like faces probably show the influence of Carl Einstein’s African Sculpture (1915), which Woollaston purchased in 1934 after reading about the book’s wide influence on modern European artists.

The painting depicts the young son of Woollaston’s friend Decimus Wells, a Mapua orchardist. Woollaston frequently used Wells’ family as models in the 1930s, and they were generally supportive of his work – although, according to Woollaston’s letters, they did not always like some of his more radical interpretations of the children. A young Colin McCahon, on the other hand, was deeply impressed by the bold modernism of this painting. McCahon acquired the work from Woollaston and kept it in his personal collection until his death in 1987, when it was given back to the Woollaston family.

Despite its potential significance in the story of New Zealand modern art, this remarkable painting has remained almost completely unknown, and has never before been published.

-- Dr Chelsea Nichols, 2018